What is Brexit?

The countdown has begun to the United Kingdom's referendum on withdrawal from the European Union. The stakes are high: if UK voters opt for a Brexit - the ubiquitous shorthand that blends the words 'British' and 'exit' - their state will become the first ever to leave the union.

That would be a landmark moment in the history of post-war European integration. It could have huge implications for the constituent parts of the UK, for Ireland and for Europe.

Why is it on the agenda?

In January 2013, British prime minister David Cameron gave a speech at Bloomberg's London headquarters outlining his ambition to recast the terms of the UK's membership of the EU.

At the time, the right-wing UK Independence Party was polling strongly, the euro zone was in crisis and Cameron’s own backbenchers - many of them ardent eurosceptics - were growing restive.

In his speech, the prime minister promised the British people that, if re-elected as prime minister in 2015, he would hold an In-Out referendum as a way of settling a question that has dogged Cameron and his Conservative predecessors.

He wanted the UK exempted from the creation of an “ever-closer union” - a guiding principle of European integration since the 1950s - and would seek the repatriation of a series of powers to the UK.

If EU member states agreed to a deal that met his demands, Cameron said, he would campaign to stay in “with all my heart and soul”.

He declined to say whether he would campaign for a No vote if he failed to secure the changes he sought.

More than a year out from a general election, and with the Tories’ coalition partners, the Liberal Democrats, expressing open opposition to Cameron’s strategy, a referendum still seemed a remote prospect.

All that changed in May 2015, when the Conservatives unexpectedly swept to outright victory at the polls. Returning to Downing Street as leader of a single-party government, Cameron reaffirmed his pledge to hold the referendum by the end of 2017.

What is Cameron looking for?

He wants to enshrine the principle of the EU as a multi-currency union so as to ensure “fairness” for non-euro countries like the UK, end the symbolic commitment to ever-closer union and make the EU more competitive.

By far the most contentious demand, however, is that migrants who move to the UK should have to spend four years there before they can claim benefits.

How receptive is the rest of the EU?

In early February, the president of the European Council, Donald Tusk, published proposals that sought to address Cameron's concerns.

Tusk had to walk a fine line, giving Cameron enough to enable him to say his key reform demands had been met without undermining the fundamental principles of the EU and thereby risking strong resistance from more integrationist-minded governments.

Tusk has proposed that the UK should be allowed opt out of the common EU commitment to “ever closer union” and he also suggests that national parliaments be given more power to block EU legislation.

If a majority of national parliaments decide a draft EU law breaches the principle of subsidiarity, they could have it scrapped.

On economic governance, the UK wanted safeguards to ensure that euro zone countries could not gang up to approve new rules that disadvantage those outside the euro.

Tusk says EU rules must not be allowed to discriminate against countries on the basis of which currency they use and exempts Britain from an obligation to participate in euro-zone bailouts. But he stops short of offering non-euro countries a veto or a delay on financial services legislation.

Migrants' benefits are the most contentious issue. On this, Tusk proposes that any EU member state which finds its welfare system overwhelmed by immigration from within the EU could apply to the European Commission and the Council to impose temporary limits on access to benefits.

“The implementing act would authorise the Member State to limit the access of Union workers newly entering its labour market to in-work benefits for a total period of up to four years from the commencement of employment.

The limitation should be graduated, from an initial complete exclusion but gradually increasing access to such benefits to take account of the growing connection of the worker with the labour market of the host Member State,” Tusk’s document says, although it has left it to EU leaders to agree at a summit in February on how long such restrictions will be allowed to last.

Member states would also be allowed to pay child benefit to children overseas at a lower rate, if the standard of living there is lower. Tusk’s proposals offer a potential compromise.

His suggestion amounts to less than the blanket four-year ban Cameron demanded. Crucially, however, Tusk says that Britain has already shown that migration is at such a level to justify emergency measures, so the UK could introduce restrictions on benefits as soon as the referendum is over.

Cameron has described the draft agreement as “the best of both worlds” for the UK.

What happens now?

Intense diplomatic and technical negotiations are taking place in the background in preparation for a summit of EU leaders in mid-February, when Cameron hopes to sign off on the settlement.

In the meantime, the British prime minister has continued his own shuttle diplomacy, visiting European capital after capital in an effort to drum up support for his position. So far the responses have been largely positive.

Germany and France have both stressed the need to keep the UK in the union. Denmark has said it does not expect the deal to be substantially amended before the summit. The Irish Government gave it a cautious welcome, as did central and eastern European states such as Poland and Hungary, which remain wary about the benefits issue.

Cameron says that if the proposals are accepted at the February summit, he will lead the pro-European campaign in the In-Out referendum.

When will the referendum take place?

Once a deal is agreed in Brussels, Cameron needs six weeks to pass the necessary legislation for the referendum and must allow 10 weeks for the campaign, making June the earliest that a vote could be held. Traditionally, British elections are not held after the start of the Scottish school holidays or before the end of those in England, ruling out July and August. Much of the speculation has centred on June 23rd.

Not everyone would welcome a June referendum, however. Politicians in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales are pressing for a date later in the year because they believe campaigning for a June referendum would cut across their proposed elections. The scheduled date for elections to the Northern Ireland and Welsh assemblies and the Scottish parliament is May 5th.

Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon says a referendum date in June would be "disrespectful" to her country. In Northern Ireland, the DUP and SDLP have also objected to a date in June.

Where does British public opinion stand?

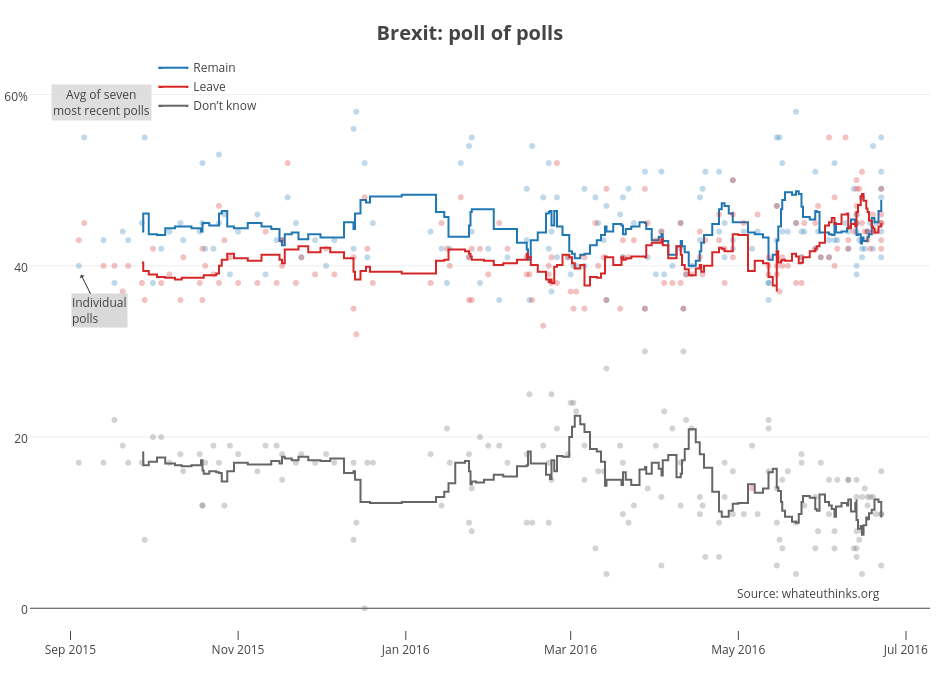

Recent polls suggest voters are split, but that support for an exit is rising. A YouGov poll published on January 31st found 42 per cent of British voters would choose to leave the bloc compared to 38 per cent who wanted to stay - the largest gap recorded by the pollster since October 2014.

How are the British parties lining up?

Cameron has said Conservative MPs will be free to campaign on either side, and by some estimates up to five cabinet members will call for withdrawal. Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn has said his party remains committed to keeping the UK in the EU but has dismissed Cameron's renegotiation as a "Tory Party drama". The Liberal Democrats are in favour of staying in while the UK Independence Party wants out.

What about Scotland and Wales?

The Scottish National Party and the Welsh nationalists of Plaid Cymru are in favour of the UK staying in. The vote in Scotland, in particular, will be very closely watched.

If the English vote to leave and the Scots are in favour of staying in, it could provoke a constitutional crisis. SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon has said such a split between voters in England and Scotland would trigger “an overwhelming demand” for a second Scottish independence referendum.

It's a prospect that alarms many politicians in London, with former prime ministers Tony Blair and John Major both warning that the UK could break up if it leaves the EU. Indeed, one of Sturgeon's predecessors as SNP leader, Gordon Wilson, has suggested that some of the party's supporters might vote for the UK to leave in the hope that it will boost Scotland's secessionist aspirations.

“I helped steer the SNP towards European policy (in the 1970s) but certain things have happened and ... I want to look at it strategically from the Scottish viewpoint. It depends on an analysis of how Scotland can better achieve independence,” Gordon said. Polls show a majority of the five million Scots would vote to stay in the EU. But the Scottish vote is dwarfed by that of England, which has 53 million and represents about 84 per cent of the UK’s population.

Is there any precedent for leaving the EU?

The Lisbon Treaty introduced an exit clause for members who wished to withdraw from the union. Under Article 50, a member state must notify the European Council of its intention to leave. A withdrawal agreement must then be negotiated between the union and that State.

But while the EU has developed complex procedures for gaining admission to the club, the practicalities around leaving are only vaguely sketched out.

That's largely because no state has ever attempted to leave. Greenland, which is part of the Danish Realm, voted to leave the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1985. A decade previously, in 1975, the UK held a national referendum on withdrawal from the EEC. On that occasion 62.7 per cent of voters chose to remain.

What would be the impact on the Republic if the UK withdrew?

Nobody knows. But the close economic ties between the two countries, and the uncertainty a Brexit would generate, have prompted the Irish Government to take a strong public line in favour of the UK staying in. "The risk relates to the uncertainty, as opposed to having any clear sense of how things will materialise over time," says Mary C Murphy, lecturer in politics at University College Cork.

Unlike the Scottish independence referendum, on which the Government maintained a studied silence, Irish Ministers have been vocal in arguing that a Brexit would damage Ireland's interests. In a speech to business leaders in London in December, Taoiseach Enda Kenny described the prospect of a British exit as "a major strategic risk" for Ireland. Minister for Foreign Affairs Charlie Flanagan has said it would be "a leap over the cliff into the unknown."

What specific concerns does Dublin have?

They stem mainly from the close economic ties between the two states, particularly in two areas. First, the UK is by some distance Ireland’s largest trading partner, accounting for 43 per cent of exports by Irish firms in 2012.

“The key question for us would be the future trading relationship between Britain and the European Union,” says a senior official. Second, the two countries’ energy markets are deeply entwined, with Ireland importing 89 per cent of its oil products and 93 per cent of its gas from its nearest neighbour.

The energy networks themselves are also closely linked: there is a single all-Ireland electricity market, which functions via a North-South electricity interconnection, and the Irish electricity and gas grids are bound to the British grids through separate interconnectors. These links improve security of supply but also reduce energy prices in Ireland because British wholesale electricity prices are lower than here.

The Financial Regulator, Cyril Roux, has said he is concerned about the impact the UK's exit from the EU could have on Ireland's banks and has asked financial institutions here to spell out how they would handle the risks that could emerge.

A report by the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) in December painted an exceptionally bleak picture of the potential economic impact. It estimated that a Brexit could reduce trade flows between Ireland and the UK by a massive 20 per cent or more, with ensuing trade barriers also pushing up the prices of UK imports to Ireland.

That’s a worst-case, almost apocalyptic scenario, and one that few experts believe would be allowed to play out. “If a 20 per cent scenario were to come to pass, then we would need some special arrangement to avoid that,” says the official. “It would not be reasonable for a country to suffer that kind of trade setback without some measure to ameliorate it.”

Will Ireland have any say?

UK citizens living in Ireland, as well as Irish citizens who lived in the UK during the past 15 years and registered to vote, can cast a ballot in the referendum. The last Irish census in 2011 showed that 288,627 people listed their place of birth as being in the UK.

A particular focus of the Irish Government’s public-information campaign will be the 600,000 Irish-born people in Britain and the estimated 2-3 million second-generation Irish.

Will Dublin openly call on voters to support the ‘In’ side?

Government Ministers will probably refrain from calling on people to vote a certain way, but Dublin’s view will not be a secret. A special unit has been set up in the Department of An Taoiseach to co-ordinate efforts, and an intensive drive to explain Irish concerns will be led by the embassy in London and the diplomatic network around Europe.

The Government's public stance has already been criticised by northern unionists. "What part of 'keep out' does he not understand," said DUP MP Ian Paisley jnr after the Taoiseach warned that "serious difficulties" would be created for Northern Ireland if the UK voted to leave the EU.

“This is a matter for the people of the UK. His intervention will be counterproductive. A fool would know that. The rush to speak should be tempered by wisdom,” Paisley said.

Would a Brexit have any impact on freedom of movement?

That would depend on the outcome of the negotiations that would follow a British ‘Out’ vote.

A Brexit could open the possibility of restrictions on people moving between Britain and Ireland for work. And given that the EU’s only land frontier with the UK would be in Ireland, it could also mean the reintroduction of passport controls at the border.

At best that would be inconvenient. At worst it would deal a hammer-blow to the border region and severely stymie North-South cooperation, which has developed in many areas since the Belfast Agreement.

Some believe this sounds far-fetched and that a bilateral deal would be struck to maintain the Common Travel Area - the travel zone that comprises Ireland, the UK, the Isle of Man, Jersey and Guernsey.

“I’m pretty sure there would be a pragmatic approach by the British and Irish Governments to finding some kind of way of dealing with potential problems on the border without going down the road of thinking about a hard border,” says an Irish official.

What positions have political parties in Ireland taken?

All the major parties in the Republic want the UK to remain in the EU. North of the border, the SDLP, Sinn Féin and the Alliance Party have indicated they will support the ‘In’ campaign.

The main unionist parties, the DUP and the UUP, are sitting on the fence and say they will only take a firm position when Cameron concludes his negotiations. The DUP MEP Diane Dodds, whose party is traditionally eurosceptic, last month ridiculed Cameron's reform proposals, calling them "thin gruel"

Would a Brexit affect the political relationship between the UK and Ireland?

It could herald an important political-diplomatic realignment for Ireland. The peace process was underpinned by a strong Anglo-Irish relationship that had “normalised” over the decades through regular contacts between politicians and officials on the European stage.

In a chapter in 'Britain and Europe: The Endgame', published by the Institute for International and European Affairs in February, Tom Arnold and James Kilcourse note Irish concerns that an EU exit would be "a significant geopolitical risk" that could pose challenges for the bilateral relationship and the fragile peace process.

A UK detachment could isolate nationalist communities in the North, they suggest. "A lot of the cross-border co-operation that currently takes place on the island of Ireland, but also between Ireland and Scotland, takes place currently through EU funding," says Anthony Soares, deputy director of the Centre for Cross-Border Studies.

“If the UK were to leave the EU and no longer have access to that type of funding... that would really leave at risk the cross-border cooperation that takes place at the moment.”

Ireland would lose an important ally within the EU. What impact would that have?

It would force Dublin to rethink how it positions itself within the EU. Dublin and London may be on opposing sides of the European debate on agricultural subsidies, but they find common cause on free trade, taxation, the internal market, financial services and justice and home affairs - issues on which the two capitals are staunch allies.

A British departure could put more pressure on Dublin to raise its corporate tax rate, for example. More generally, “the balance of power within the EU would shift to the south and the east, where Ireland has few natural allies on strategically important issues,” write Arnold and Kilcourse.

Many would see that as offering positive side-effects for Ireland, by forcing Dublin to forge closer alliances with France and Germany and to adopt a less Anglo-centric stance in world affairs.

"In the 70s, when we joined the then EEC, there was a lot of excitement in the Irish political elite - this was very much Garrett FitzGerald's view of the world - that it meant we were no longer an island behind an island, that we had our own place, independently of Britain," recalls prof James Wickham, professor emeritus in sociology at Trinity College Dublin.

“That idea of being an independent and specific country within what has become the EU has actually watered down a bit over the last couple of decades, because of the growing interdependence with America.

“When I started teaching in Trinity in the 70s, bright young students wanted to go to Europe. By the 90s, that didn’t exist. They had gone back to the Anglo world. It might very well have the consequence of pushing Ireland into more involvement with European politics and more involvement in the European idea.”

Are there ways in which the Republic may stand to gain from a Brexit?

One way in which Ireland could gain economically is through foreign direct investment (FDI). If the UK cut itself off from the EU, a market of 500 million people with a combined GDP of €13.5 trillion, Britain would be a far less attractive place for firms to invest in.

Research cited by Edgar Morgenroth, associate research professor at the ESRI, shows that EU membership increases FDI from outside the EU by 27 per cent. Some foreign firms could well opt to leave a post-Brexit UK. Similarly, British firms might seek a new foothold in the union.

In both cases, Ireland would be well placed to benefit. Morgenroth estimates that Ireland could attract $6.6 billion of additional inward investment, although he adds that this would be offset to some extent by the reduction in the value of Irish firms’ own investments in the UK.

What kind of relationship would the UK have with the EU if it voted to leave?

That would be up for discussion. Would the UK follow the example of Norway, for example, which remains outside the EU but whose membership of the European Economic Area allows it to stay within the single market so long as it applies the vast corpus of EU laws in its domestic legislation (including rules on freedom of movement)?

Or would it seek to follow the Swiss model, whereby instead of signing up to the entire body of EU laws a state can sign a series of bilateral agreements that add up to the same thing? If the UK followed either the Norwegians or the Swiss, the changes for Ireland would be minimal.

At the other extreme would be a complete severing of ties to the EU, but given that the impact could be catastrophic for the British economy it is one of the least likely outcomes.

Far more plausible a scenario would be the negotiation of something altogether new, perhaps along the lines of the "privileged partnership" once broached by German chancellor Angela Merkel as a way of binding Turkey to the bloc without giving it full membership.

Either way, a British No to the EU would take a long time, and a lot of creative diplomacy, to put into effect. “There will be a period of about two years when there will be an exit strategy put in place for the UK to remove itself from the structures,” says Murphy.

It will be a discussion from which the UK will be partly absent, she adds, leaving the rest of the EU to decide how to strike a balance between two imperatives: on the one hand a desire to keep trading with the British and on the other a determination not to reward London for leaving, which could encourage others to follow suit.