The murder of the Labour MP Jo Cox has paralysed Britain's EU referendum campaign, with both sides suspending campaigning as Westminster remains frozen in shock. Nobody can predict what impact, if any, the murder will have on the outcome of the referendum or if the pause in campaigning offers an advantage to either side.

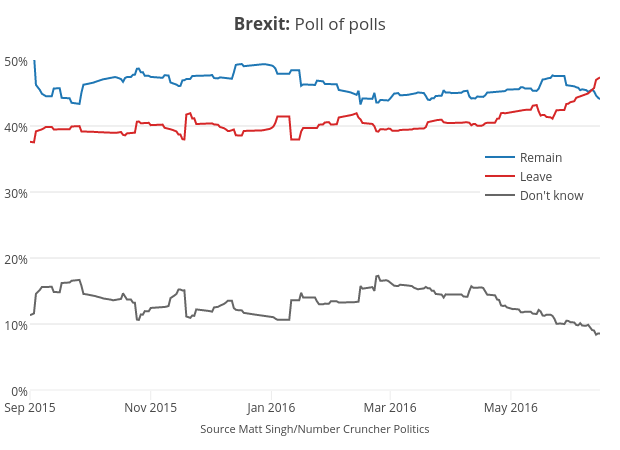

The hiatus comes as Leave has moved clearly into the lead, with four out of the five latest polls showing voters backing Brexit by a margin of between six and eight points. The fifth poll, by ComRes, shows Remain ahead by just one point, down 11 since its previous survey.

“Clearly, Leave are winning, and if nothing changes they will win,” says Charles Grant, director of the Centre for European Reform and an expert on Britain’s tortured relationship with Europe. “We all know that psephologists say there’s a last-minute shift to the status quo in the final days of a referendum campaign. I’m waiting for that shift to appear, but it hasn’t appeared yet. If there’s been any shift in the last two weeks it’s been in the other direction.”

The official Remain campaign, Britain Stronger in Europe, is a cross-party political coalition that also includes figures from business within its leadership. The Remain campaign’s strategy has been determined above all, however, by the chancellor of the exchequer, George Osborne.

Osborne is not only David Cameron’s closest ally but also his most trusted political strategist and the author of the general-election playbook that last year won an unexpected majority for the Conservatives. Osborne believes that the same strategy, a relentless focus on the economy and on the risks involved in rejecting the status quo, will persuade voters to reject Brexit next Thursday.

As the polls point towards Brexit, complaints within the Remain campaign about the chancellor’s strategy are becoming louder, and Grant believes that although the economic argument is necessary, it is not sufficient.

“Economics is not enough,” he says. “They’ve got to have a narrative about Britain leading Europe, shaping Europe, winning in Europe, Europe doing good things under British guidance and tutelage. They’ve got to make people feel positive about Europe.”

The Boris factor

Although Remain was ahead for most of the campaign, there were signs of trouble from the moment in February when Cameron returned from Brussels after his renegotiation of Britain’s EU membership. He won as good a deal as he could, with modest changes to rules on benefits for EU migrants, an arcane agreement about the relationship between EU states that use the euro and those that don’t, and a largely symbolic exemption for Britain from the commitment to “ever closer union”.

The British press dismissed the deal as derisory, pointing out how far short it fell of the “new settlement” between Britain and Europe that Cameron had promised in his Bloomberg speech three years ago and of specific policy commitments in last year’s Conservative Party manifesto.

Within days of the deal dozens of Conservative MPs said that they would campaign to leave the EU, among them six cabinet ministers, including Cameron's friend and close ally Michael Gove.

Gove’s decision was followed by the political striptease of Boris Johnson’s announcement that, after much agonising, he too would be campaigning for Brexit. The most popular politician in the Conservative Party, the former London mayor also appeals across party lines and is a magnet for television cameras as well as for voters.

The Leave campaign now had a figurehead capable of capturing the limelight and pushing the polarising figure of Nigel Farage, the Ukip leader, into the shadows. But if Farage was sidelined, his signature issue – the need to leave the EU in order to control immigration – moved to the centre of the Leave campaign.

No response on immigration

Canvassers on both sides report that immigration is the issue that voters raise most frequently, and it is an issue that plays very well for Leave. In working-class, traditional Labour strongholds, voters complain that hospitals, schools and other services are overburdened, and they blame the fact that migration from the EU can’t be controlled.

Labour found itself tangled up in knots over immigration this week, with the party’s leader, Jeremy Corbyn, defending the free movement of people within the EU while his deputy, Tom Watson, said that Britain should seek to change the rules so that numbers could be limited.

The Remain campaign has found no effective response on immigration, depending instead on parading a procession of national and international luminaries in dark suits to warn about the economic catastrophe that would follow Brexit.

The problem is that many voters trust neither Osborne nor Cameron and either don’t believe the experts’ warnings or don’t care.

“There’s a global trend in the north Atlantic area towards voters distrusting elites and establishments and those who benefit from globalisation,” Grant says. “And those who think they lose from trade and immigration don’t care about the overall economic benefit at a national level, because they don’t see that benefit.

“And there are a lot of losers, which is why people support Donald Trump and they support Nigel Farage and Le Pen and Geert Wilders.”

As they savour the latest poll results, Leave campaigners can't believe their luck. Many leading Brexiters are still convinced that much of their support will evaporate in the polling booth as voters consider the cost of taking a leap in the dark outside the European Union.

‘Politics has changed forever’

Win or lose, however, the Leave campaign will have accomplished something remarkable if close to half of the British electorate back an idea that was considered until recently to be frankly eccentric.

At a Vote Leave rally in the Kent coastal town of Ramsgate last week the former Northern Ireland secretary Owen Paterson told supporters that the referendum had already changed the entire dynamic of British politics.

“Until now the concept of wanting to leave the European Union has been mocked by the establishment. It is completely inconceivable that the discussions that you are getting daily on the BBC could have happened even six months ago because people who wanted to leave the European Union were nutters, were racists, freaks, weird members of the right-wing Tory party,” he says. “What’s happening now, of course, is that it’s becoming mainstream. Millions of immensely sane, respectable people are going to vote to leave, and you won’t be able to put that genie back in the bottle. So, whatever happens, politics has changed forever.”

Rise of the Eurosceptics

Only a handful of public figures in Britain talked about leaving the EU until 1992, when Denmark voted in a referendum against the Maastricht Treaty. After winning a few concessions the Danes reversed their decision in a second referendum, but that first vote allowed Conservative Eurosceptics to dream that they could win a popular vote against Europe.

In the early 1990s bitterness on the Tory backbenches over the defenestration of Margaret Thatcher fuelled the Eurosceptic revolt against her successor John Major. After 1997, when the Conservatives suffered their greatest electoral defeat for more than 150 years, the Eurosceptics began to account for an ever larger share of the party’s MPs.

"They started to take over the Tory party little by little, and then David Cameron was forced into this referendum because of Ukip," Grant says. "In a way he was right, because if he hadn't offered the referendum Ukip would have done even better at the last election, and it probably would have cost him his majority. So he really had no choice but to offer a referendum."

The final days

Remain campaigners are gloomy as they face into the final days of the campaign, but they have not given up hope of snatching a last-minute victory. The pollsters’ failure to predict Cameron’s election victory last year offers some Remainers hope that they are underestimating the number of risk-averse voters who may not like the EU but will draw back from voting to leave.

Despite the self-proclaimed fervour of its supporters, Vote Leave’s events have been poorly attended, with only Johnson attracting big crowds. Paterson’s event in Ramsgate, a Brexit stronghold, had an attendance of 28, and other MPs attract fewer still. Vote Leave has invested heavily in data harvesting and social media, as has the Remain campaign, but Remain appears to have a bigger and better-organised ground operation.

Labour MPs say that although immigration remains the biggest issue on the doorsteps, it has receded a little in recent days. Some Remain campaigners fear that the moratorium on campaigning following Cox’s murder will mean they won’t have enough campaigning time left to turn the polls around. Others hope, however, that the sombre mood since her killing will cause voters to stop and think before they march towards Brexit to the beat of an anti-establishment, populist drum.